As an officer and beadle of the Court of Requests of Enfield, a major part of John Draper's job description was the collection of small debts from people who resided within the Court's jurisdiction. One of John's acquaintances was Richard Thomas, a schoolmaster at nearby Barnet, who often accompanied John on his debt collecting missions.

On the morning of Thursday, August 8, 1816, John Draper set off from his home in Chase Side, Enfield, accompanied by his small dog, and made his way to find Richard Thomas to invite his participation in the day's activities. The two men began their quest at about 10:30 a.m, and located one of their targets, a man named Daniel Chappel. He owed the sum of 2 pounds 18 shillings and 9 pence, and John Draper and Richard Thomas arrested him and took him to the 'Robin Hood and Little John' at Potter's Bar to settle the debt. Chappel sent for Mr Reynolds, his attorney, who paid the said debt on his arrival.

It was at this time that John Draper pulled out the little red pocket book that was to become instrumental in the trial of his murder. It already contained what was described as " a large roll of bank notes" , to which John added Chappel's contribution. Mr Reynolds the attorney actually commented on the quantity of money, and voiced his surprise that Draper was not scared to carry that much money around with him.

That business completed, John and Richard made their way to the White Bear Public House at Barnet, and settled themselves in for a bit of a session. Richard Thomas left John there at 7:10 p.m, and later commented that at this time the beadle was "neither sober nor drunk".

A hairdresser named James Smith dropped into the pub for a pint of porter, and despite not knowing John Draper previously, the two men obviously bonded over a friendly drink and James accompanied John when he decided to move on to another pub. The motive for James' friendship may be explained by the fact that John Draper had a horse and cart and had promised James a lift part way of his journey home to Cheshunt.

After another pint of beer, the pair moved on again, this time stopping at the Bald-faced Stag at Enfield Chase. The time was about 8:30 p.m., and being in his home territory, John settled in for a few serious after-work drinks.

Amongst the other drinkers in the pub at the time were a group of pugilists- professional fighters who were residing and training at the Bald-faced Stag. One of these men was a big black man called Samuel Robinson, and after consuming three glasses of gin and water, John was full of enough Dutch courage and inflated self-belief to start antagonising the fighter.

He went so far as to pull out the red pocket book again and offered to place ten or twenty pounds to lay a bet if Robinson would fight him. Robinson would have taken one look at the 55 year old drunk man and known the money would be like taking candy from a baby, but he declined the offer and told Draper he would "take the law of him" if he struck him.

James Smith started trying to convince John Draper to leave the pub and start for home, but his words fell on deaf ears, and at about 10 p.m James had had enough..he bid John goodnight and headed out the door.

After walking for about twenty minutes, James must have been amazed when he was passed on the road by John Draper's horse and cart...minus John Draper! He climbed in, turned the horse around and returned to the Bald-faced Stag. Finding John still drinking and in fine form, James extracted a promise from him that they would leave when he had another "glass or two". Another hour passed, during which time the horse again scarpered for home from its position out the front of the pub. James and John went looking for it, and when John spied the hostler of the Bald-Faced Stag he grabbed him by the collar and demanded to know where his horse and cart were.

Roberts, the poor old hostler, protested his ignorance and stated truthfully that he knew nothing about them. Drunk and obnoxious, John started to shake Roberts, and after a struggle they both fell to the ground near the front door of the pub. Upon gaining his feet, John looked around for somebody else to fight, and attacked a haymaker who had been watching the scuffle. In defence the haymaker gave John several pushes to get him away before they were separated by James Smith.

Mrs Tuck, the publican's wife, took John into the pub and sat him in the parlour. James Smith was still with him, and other people in the parlour at the time were Robinson the fighter, a butcher named Walpole, a constable named John Holmes, James Tuck the landlord of the Bald-faced Stag and several others. Another round of drinks was partaken by John and his offsider James Smith, and then two other men, Richard Crouch and Peter Saunders, both pugilists, joined the group in the parlour.

For the last time James Smith entreated John Draper to accompany him home, but again his suggestion was refused, and at about 11 o'clock the two parted company again, this time for good.

James Smith started on the road to Hoxton, and about half a mile from Enfield he came across the escape artist horse for the second time. Despite not knowing exactly where John Draper lived, James climbed up into the cart and gave the horse its head, and like an equine version of Lassie the beast stopped right at John Draper's front door.

Upon knocking at said door and discovering that it was indeed the Draper residence, James had the job of informing Frances Draper, John's wife, that he had left her husband at the Bald-faced Stag. Frances, most likely well-used to such a situation, merely commented that she hoped her husband would take lodging there for the night as it was so late.

Back at the Bald-faced Stag, John Draper was drinking with John Holmes from Tottenham, a man who had also at times accompanied him on his debt-collecting rounds. It was agreed that Holmes should go home with John in his cart, the former not realising that this was impossible as the horse had made its own way home without its master.

At some time around eleven o'clock John Holmes realised that John Draper was no longer in the room, and that Robinson, Crouch and Saunders had also left, along with the landlord, James Tuck.

John Holmes went outside to see what had become of his lift home, and when he could find no sign of John Draper or his horse and cart he returned inside and proclaimed to his fellow drinkers "I believe Draper has given me the slip, for I intended to go home with him and he is gone."

John Holmes bought himself another drink, and around midnight left the Bald-faced Stag, having not seen John Draper or the pugilists again that evening.

Passing the Bald-faced Stag at around midnight was a young man by the name of Charles Thompson. He was the servant of Mr Paris, who resided about a quarter of a mile from James Tuck's public house. As he was passing, he saw four men , led by James Tuck, come running out the front door. There was a full moon that evening, and the moonlight ensured that there was no mistaking the identity of the landlord. Charles Thompson heard Tuck say "Damn his old eyes- he has gone round here. He has gone this way."

One of his companions, none of whom were known to Charles Thompson, replied " We will give him a good hiding, and will kick him." Charles watched as the four men went into a field next to the pub, then continued on his way home to Cock-Fosters.

The next morning, at a little after 5:15 a.m, servant Mary Holburn was awakened for the day's work by her master, James Tuck. At seven o'clock she went to the well in the field next to the pub in order to draw water, a task she completed every morning. She noticed that a piece of the wood forming a fence around the well had been broken, and that the water in the well seemed very "thick", but continued to dip the pail down through the well opening.

Mary then noticed a man's hat in the well, and realised that she could see part of a man's face. She fled back to the Bald-faced Stag, crying to James Tuck "Good gracious, Master, there is a man in the well!" James at the time was letting the chooks out of the henhouse, and his reaction , according to Mary, was "Good gracious, I suppose it is the poor old hostler."

Going to the well and observing that a man's body was indeed down there- strangely enough in an erect position as though it was leaning against the pipe of the well- James Tuck went and found the Negro fighter, Samuel Robinson. Again according to Mary Holburn, James Tuck said to the fighter "Good gracious! Robinson, there is that poor old hostler in the well."

With assistance from Robinson and two of the other pugilists, Saunders and Crouch, the body of the drowned man was removed from the well and carried to the brew-house. It being ascertained that the identity of the corpse was not the hostler, but troublesome John Draper from the previous night, James Tuck sent for David Draper, John's younger brother.

David arrived with John Draper's son, David Draper, who was about 28 years old and a shoemaker . They asked James Tuck what had become of John's property that he was carrying the night before, and were told that the landlord had no idea what property John had been carrying, and that whatever had been on him was on him still.

David Draper and his Uncle searched John's body and found two pocketbooks, neither of which was the red pocketbook that had been freely shown off the during day and night previous. Both pocketbooks contained nothing but summonses and orders from the court. A purse was also found that contained only nine shillings and a halfpenny...there was absolutely no sign of the red pocketbook with its large roll of banknotes collected by John Draper on behalf of the Court of Requests.

As the news spread of John Draper's death, great excitement and interest was exhibited by the locals, and no doubt theories of how he had met his demise were flowing thick and fast. It was noted in an article printed in the London Times on August 14 that for the entire day after John's body was discovered down the well, the inn yard was thronged with people.

An inquest was summoned and gathered at the Bald-faced Stag to view the body in addition to the well in which John Draper had been found. The Coroner also called a great many witnesses to give testimony of the chain of events that had unfolded as John Draper had gone about his business the day and night before.

Local Enfield surgeon, Joseph Clarke, was called to examine the body of John Draper. On examining the head, Clarke found bruises about the face, on both cheeks and under the left ear, all appearing to have been made by a blow from a fist. During the examination James Tuck told the surgeon that John Draper had been fighting the night before with one or two men. This fact, combined with John having been found down the well, led Clarke to declare a verdict of accidental death. He stated that he had found no marks of violence that could have occasioned Draper's death.

This was ruling was accepted by the Coroner's Jury, and it seemed as though John Draper's death was a simple open and shut case of a drunk man falling down a well whilst stumbling past in the dark.

The article in The Times stated:

" The Coroner, in substance, observed, that although a great suspicion had arisen that the deceased had been robbed of property to a large amount, and had afterwards come to a violent death to screen that robbery; yet however just might be the grounds for the first of these imputations, the second was not so clear. The deceased was excessively intoxicated, and in his way to the yard,where his cart had been left, must necessarily have passed near to this well, which was unenclosed in the front, and into which he might have fallen by accident; and there was a difficulty in conceiving that he could have been forced into this well, unless he had been first violently deprived of all sensation, in which case some external marks of injury would have been visible. Looking at the situation of the place, and the dimensions of the well, there are difficulties either way, but the Jury would decide on the superior probability. Verdict: Accidental death."

Obviously, however, the missing pocketbook was ringing alarm bells for John's family. Just as two undertakers were about to place John's body in a coffin for burial at St. Andrews as specified in his will, his brother David and son David came forward and insisted to the Coroner that it be re-examined as they had found a violent bruise under the left ear, and some blood on John Draper's clothing.

Mr. Unwin, the Coroner, acted upon this information immediately, instructing Joseph Clarke the surgeon to "open and carefully examine" the body of the deceased, and to report to him the result of this second examination. He also told John Draper's brother and son that if any evidence of violence upon the body was found, he would engage the police magistrates for further investigation of the case.

It was August 13th when the Coroner requested Joseph Clarke to re-examine John Draper's body, four days after it had been pulled from the well. The state of the corpse was described by the surgeon as "putrid", so it must have been a particularly unpleasant task to carry out a post mortem upon it.

On the second examination, Clarke took more care to closely examine the bruises and marks on the face and neck, and this time came up with a different conclusion. In particular, he stated that the blows on John Draper's neck were "sufficient to have rendered the deceased insensible, more particularly so in the case of a man who was drunk."

Upon opening John Draper's skull, the surgeon found nothing to make him think that the cause of death had been from the blows. He made comment, though, that if John Draper had been found dead on the ground instead of in the well, he would have attributed his death to the blow on his neck.

A second surgeon had been called in to make his own judgement during the second examination. Fellow Enfield surgeon William Henry Holt agreed with Joseph Clarke's second judgement, feeling that the evidence of a blow under the ear was especially significant. He stated to the Coroner that he "had no doubt but that a man who had received such wounds would have been finished, and afterwards thrown into the well."

Charles Brown and William Reed, two senior police officers from Hatton Garden, had been sent to Enfield to investigate John Draper's death. The evidence from the second examination of the body, coupled with the missing red pocketbook and testimony given by Charles Johnson concerning James Tuck and the pugilists following John Draper out into the well field on the night of his death, was enough for the two officers to require the Coroner to hold a new inquest that day on the body.

The result of this inquest was that the accidental death verdict was thrown out, and James Tuck, landlord of the Bald-faced Stag, was taken into custody by Charles Brown and William Read and charged with the wilful murder of John Draper.

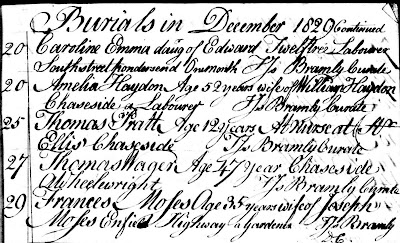

On Friday, August 16, 1816, the body of John Draper was finally laid to rest in St. Andrews Church yard, Enfield. The following Monday, August 19th, James Tuck appeared in court for the first hearing of his murder charge. The session lasted for four hours, after which Tuck was remanded in custody for further examination.

He was back in court three days later, and after the Magistrate had examined all of the evidence and witnesses, he informed Tuck that because the case was "so intricate and mysterious' it was his duty to research it even further. James Tuck was again remanded.